This is another cross-post from my new website which is devoted to my writing.

Reading my favourite author (though not my favourite book) in the past couple of weeks has transported me to the land of my youth. Stephen King is one hell of a writer because he tells the truth about human nature, and as much as I like a good spine-tingler, I think that the element of horror is only a prop that’s all too often mistaken for the defining feature of his work. Christine is a story about a car and about teenagers growing up in roughly the same era as myself, but on the other side of the globe. Maybe because I spent part of my childhood in England where I’d been primed for a worldview so different from the Soviet one, I could see myself as one of King’s characters. Although I didn’t share their actual experiences, I can easily slip into their mindset as into well-fitting clothes. This trick of the mind is not unique to immigrants and expats. I think that with age, everyone to some extent replaces what really happened with what might have happened. It’s a universal feature of human memory.

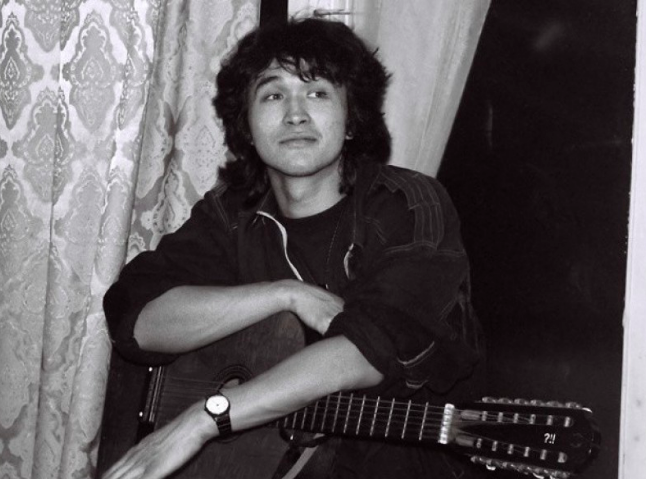

Familiar though it can feel to me, the reality of American teenagers in the late 70s bears little resemblance to the youth that I actually lived out, although the passage of time and the shifts in my worldview have made it feel like that young life was someone else’s. I think about the experiences on which Soviet youth of my generation missed out, for better or for worse. The first thing that comes to mind in the wake of Christine is that there was no culture of driving lessons, or of getting our first car. Most people didn’t drive or own any car, first or subsequent. Related to this is freedom of travel in general. We were painfully aware of our inability to see the world beyond the Soviet bloc; in the late 70s and early 80s, travel outside the iron curtain was not yet an option for most. We were curious about the free world, envious of the people who lived in it, and hungry for any tangible evidence of life on the other side. While it wasn’t readily available in stores (except for The Beatles and artists like Mireille Mathieau), pop and rock music from Western Europe made its rounds in the form of cassette tapes privately copied in a chain reaction. The discotheques we danced at played mostly Western music. But we had our own rock heroes, my favourite being the lighthearted and melodrama-free Viktor Tsoi with his darkly honest songs. These artists weren’t ‘underground,’ they weren’t persecuted, their songs weren’t about social protest but about eternal subjects like war and love and dying and living.

Everyone knows there was no sex in the USSR, right? Well, there wasn’t, and there was. Sex was the province of people much more attractive and confident and carefree than the likes of us high-schoolers. We vaguely knew, or hoped, that it would happen to each of us at some point, but it was never heralded or ushered in. There was no expectation of a sex life as part of our identity. Nobody really talked about it in a romantic sense; the sex ed classes taught by our matronly biology teacher involved separating the class into boys and girls, and instructing each group separately about the facts of life. We were naive and clumsy as hell when it came to dating, which usually didn’t even happen in high school but was put off until the university years. School was for children, even if the children were getting on in years, and children don’t date–they learn. Nobody had to worry about whom they’d pair up with for the prom: high school graduation night wasn’t about couples. And, prom king and queen? Put that out of your mind completely. Later we blamed this sexual cluelessness for being generally unprepared for relationships and married life; but later still, when we learned how surprisingly unhappy people could be in the free world, we wondered if we were actually that much worse off.

Most importantly, we missed out on this thing called teenage angst. It was simply not an expectation. And what did we have to be angsty about? How was that even possible at the beautiful dawn of our adult lives, with so much to do and everything still ahead? I think it was similar to the anticipatory panic over the allegedly hellish difficulty of learning certain skills. If you somehow missed that memo, you might just breeze right through the experience without ever suspecting that it was supposed to be hard! That’s pretty much what happened to Soviet youth of my generation with regard to this exotic beast called teenage angst. Of course we were living under the cloud of the Cold War, and of course we were afraid of the atom bomb. Terrified, in fact. The only nightmares I’ve had in my life featured that very bomb. But we were surprisingly unconcerned over what path each of our lives would take on a personal level. A proprietary blend of Russian fatalism and Soviet collectivist mentality had taken care of that. Preoccupation with one’s self was not only frowned upon, but openly shamed. We wore uniforms to school, and girls were discouraged from wearing earrings so as not to emphasize the very real distinctions in wealth and social status. Cynicism was met with stern and sincere reprimand from teachers: we simply had no business being cynical at our age and with the opportunities we’d been given.

If we were naive and innocent in some ways, in others we had to grow up much faster than our Western brethren. There was no practice of self-searching upon graduation from high school, which was followed, without any break and during the same summer, by entrance exams to the university of one’s (or one’s parents’) choice. Right there and then, we were expected to know what we wanted to do–or didn’t terribly mind doing–for the rest of our lives. At the time, nobody suspected how much the world would change in a couple of decades and how common it would be to acquire new skills, new degrees, and new careers. There was a finality to a decision we were expected to make at the age of seventeen, and one that I appreciate only now.

Since I opened with Christine, here’s my Soviet counterpart of literature about young adults, one that had a gentle and profound influence on me. The title of the book is Wild Dog Dingo, Or a Novel About First Love, by Ruvim Frayerman. The love story is chaste but realistic. This book was an expected summer read rather than part of the high school core curriculum, and nobody balked at it in contrast to some of the in-your-face books with conspicuous moral and social lessons. Much later, I was surprised to learn that the book was first published all the way back in 1939, although it felt like the events were taking place in our time (i.e. the late 70s and early 80s); this only means that the book is truly timeless. It’s unfortunate that this classic of Soviet young adult literature was never translated into English. (Perhaps I’ll undertake that project myself at some point.) The movie version captures the spirit of the book, so I recommend it to those who want a taste of Soviet romanticism in cinema. There’s no English soundtrack, only subtitles. If you watch it, I’d love to engage in a discussion about the movie–or Viktor Tsoi’s clip–in the comments below.